Interview

The route to FAR leads to the “Zentralbüro”, an office-share on Alexanderplatz in Berlin. Artists, architects, musicians, scientists, and journalists all work here in the former premises of the Polish Cultural Center. Prefab ceilings and walls with color glass squares exude the charm 1970s East German architecture. Through the windows of the enormous meeting room you can enjoy the view of the TV tower. Marc Frohn is sitting opposite me, full of expectation. There is a laptop on the table that connects us with Mario Rojas Toledo in Santiago de Chile.

Mario and Marc, you work on three continents. What’s the advantage?

Marc:

To put it loosely, when we started up with FAR in 2004 the situation was as follows: In South America you could build, in Germany publish, and in the USA debate things at colleges. Each in its own way is a good starting point for pursuing architecture.

So you are not primarily bothered about building?

Marc:

It goes without saying that we enjoy building but in my opinion as an architect you shouldn’t restrict yourself to it. Architecture is not just about putting up a sheath that provides all the right functions. Architecture can just as well communicate when published as an idea. Our output can be a building, but it can equally be an article, or an image.

What does that depend on?

Marc:

On the context. Having to do things is always a good thing. We don’t want to reduce our assignments to just technical aspects. We’re far more concerned with raising architectural questions that are of significance for the era we live in.

Which questions would those be?

Marc:

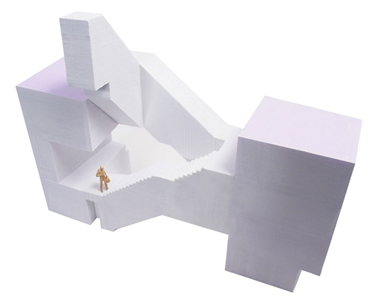

With the Wall House in Santiago, for example, we addressed the significance of walls as an architectural boundary. Our competition entry for the German Embassy in Belgrade looks at security.

On your website you ask what happens when German building technology meets Chilean craftsmen. What’s the answer?

Mario:

In Chile, there’s no classic way of building the way there is in Germany. If the workers do not build houses, they mow lawns or wash cars.

Marc:

For the Wall House there were two categories of worker: Those who could weld, they got 20 dollars a day, and those who couldn’t, and they got eight. The structure and specifications of the entire house are such that it is designed to be built by ten people. Only the wooden frame was prefabricated in a factory.

You offer the Wall House for sale on the Internet an. For how much?

Mario:

On the Hometta platform for EUR 2,000we sell the rights to work with our design. Anybody can do something with it in line with local circumstances. There is one condition, however, namely that we be allowed to make images of whatever they make in order to document the “family tree”.

Marc:

The DNA of the Wall House lies in the principle of breaking walls open, not in the materials,

we could have used others. We want to know what happens when as authors

we surrender control at a certain point. Things only become intelligent when others

think them through further.

Does that work?

Mario:

The Wall House is not a bestseller. It’s not that easy to separate architecture from personal tastes, it’s not something you just buy on the Internet. That said, one version of the Wall House is just being built in the Netherlands though. On the island of Texel, as part of a holiday home complex.

How do you distribute the work?

Mario:

We complement each other very well. I’m more the technical developer, Marc does the concepts. He has an incredible imagination when it comes to developing architectural approaches, as he tends to see each challenge in a different light.

Marc:

Mario is the “Chilean terrier” who really gets his teeth into a problem and doesn’t let go until it’s solved. All projects have always been handled in both studios, in Berlin and Santiago. It’s pretty crazy, you have 16 people working together every day, some of whom have never met one another.

Where do your employees come from?

Marc:

In Berlin our employees have so far been from Australia, Greece, the USA, Portugal, and Spain.

Mario:

We have lots of architects from Chile and Columbia working for us, and from Germany as well.

Do you actually see yourselves as a German studio?

Marc:

The nice thing is that we see ourselves as both insiders and outsiders. It’s very important to us to have a view from the outside.

How would you describe your view of German architecture?

Marc:

We Germans tend to solve problems technically. That’s a typical engineer’s mindset. For me, German architecture culminates in the term “passivhaus” (passive house). It says a lot about how we approach architecture here.

Mario:

Do you know how they improved the lighting at the bus station in Aachen? Typically German: They fitted a really complicated mirror system. Now imagine the same bus station in Mexico City. The Mexicans would probably paint it in a bright color.

Marc:

I get the impression that in this country critical reflection on the technical and social gets far too raw a deal in architecture. The engineering side of things definitely has the upper hand. I don’t want to be nostalgic, but there hasn’t always been this imbalance.

Marc, what was your experience in the USA, where you spent six years studying and teaching?

Marc:

As a student I was impressed by the seriousness with which, for example, theory was addressed at Rice University in Houston. On the one hand, they read the classics, such as the Frankfurt School and the French philosophers, and at the same time, there were any number of interesting discussions.

I found the strict division between theory and practice in the USA a problem. All too seldom did a productive conflict between the two sides evolve. And it’s precisely this conflict that interests me in our work.

Mario, you teach at the university in Santiago and saw to your local building sites. What can you say about Chile?

Mario:

There are now three generations of Germans living there, and they have left their mark on the country. Chile’s architectural scene has come on enormously in the last ten years. A lot of people who studied in Europe or the USA during the Pinochet dictatorship are returning and bringing new ideas with them. On top of which the people are pretty easy-going with regard to the future, as opposed to Europe. I would like to see a German developer working with an architect under 30 years old and not having headaches about it. In Germany you’re seen as a risk, whereas in Chile people see you as potential. We’ve benefited from that. The fact that we are now designing the Goethe Institute on behalf of the Federal Republic of Germany was only possible because we’d previously been able to build the Wall House in Chile.

What role do competitions play for FAR?

Marc:

Competitions are a good reason to concern yourself with certain topics. We’ve never landed a project on the back of a competition, but we’ve come up with a load of ideas for the studio.

Lots of architects make their design processes comprehensible in diagram form. On your website I noticed that you illustrate lots of projects using images merged together, for example the sun rising behind the Wall House or the acoustic curtain closing in the Goethe Institute. What is behind that?

Marc:

I am cautious when it comes to the cooking recipe method of teaching with diagrams. For the most part they fail to reveal the reasons for the decisions that resulted in the design. It often seems that there was only perfect solution that left no questions open. We tend to see ourselves more as architects who make the rules for a process, who create a framework in which architecture is possible. It’s constantly changing and we want to portray that flux.

Interview: Friederike Meyer

Friederike Meyer studied Architecture in Aachen and graduated from the Berlin School of Journalism. She is a member of the editorial staff of Bauwelt.

Project management: Andrea Nakath