Profile

It was eight years ago that Mario Rojas Toledo, who was born in 1973 in Houston, Texas, touched down. On his way from Germany to Mexico he had organized a stopover to visit his college friend Marc Frohn (born in 1976). They had often worked together while studying for their degree at RWTH Aachen University, then Marc had departed, first for Naples, to Rem Kohlhaas, and later for the USA, where he gained his Master’s. Mario had in the meantime worked in Oscar Niemeyer’s studio, at gmp, and for Eun Young Yi. His family comes from Chile, and he has a large circle of acquaintances. And he now had an assignment under his belt. A residential building for a maximum of EUR 100,000. The 5,000-square-meter plot of land was on the outskirts of Santiago de Chile. The clients were due to retire and wanted to leave Germany and return to their home country. The two architects spent three days discussing how to go about it. Then they founded FAR.

Two people, two computers, two continents and Skype, those are the circumstances under which the home was built. While working for other companies by day, Marc Frohn at b&k+brandlhuber&co in Cologne, Mario Rojas Toledo for Bernardo Gómez-Pimienta in Mexico City, at night they put their minds to the relationship between the interior and the exterior, to spatial boundaries, and material. They designed their clients’ retirement home around a concrete core, gave it several layers and created rooms that turn all conventional ideas upside down. They called their work Wall House, an homage to the famous design by John Hejduk, who in 1969 had asked himself similar questions. The building became a crowd-puller. When the construction workers began pouring the concrete, rumors spread in the neighborhood that it was going to be a high-rise. When they were fitting the polycarbonate imported from Germany around the wooden shelves, there was talk of a greenhouse. And no sooner had the neighbors got used to the sight than FAR stretched a piece of fabric over it which, during the course of the day, changes from a transparent skin to a mirror and which is normally used for cultivating plants.

Not only the clients and their neighbors were fascinated by the strange object that had been built on the outskirts of the city. The Wall House was featured in magazines the world over, was shown in exhibitions and on TV, and was published in books alongside projects by heavyweight such as Zaha Hadid, Toyo Ito, and Herzog & de Meuron. Over night FAR became famous as the German architects was had made it big in Chile. With their very first project. Prizes in Germany, Great Britain and Italy, an appearance at the Biennale in Venice, and invitations to competitions all followed.

In the meantime FAR has 16 employees. In Santiago de Chile Mario Toledo Rojas runs the operation, in Berlin Marc Frohn, in Los Angeles one of them takes care of marketing the Wall House, which they offer as a construction plan on the Internet, thereby taking up a current topic of discussion. Is a house a customized product or a prototype? And is there perhaps something in between? FAR do not regard the Wall House as a solution, but as a model.

It is the basic questioning of the assumptions innate in assignments, of “turning things inside out”, as Marc Frohn refers to it, which characterizes their projects. Nor are the designs FAR submits to competitions always considered to be a solution, there are no “precise contours with restrained facades”, as juries like writing in their judgments. FAR’s proposals are nothing if not provocative.

For the new German Embassy in Belgrade they submitted, among other things, two images. One shows the facade overlooking the road with what appears to be a finely-woven aluminum foam mesh, while the other shows the facade after an arson attack. This was their response to the competition stipulations, which had 50 pages of security two pages of accompanying program; in their opinion it was a hypothetical

situation, which had to be designed..

Where many an architect thinks in terms of the number of storeys and window formats, FAR initially consider how they can derive an overarching theme from the assignment. In this context the local circumstances are a welcome opportunity. Building regulations, for example. When they were adding another storey to a home in London they were confronted with the “right to light”, a regulation in England that exists in its own right and is independent of building laws. It states that with any window that is older than 20 years, 0.2 percent of the sky must be visible at table height from the room behind. Or something like that. FAR checked the complicated calculation for the 27 windows in question they had been presented with by the, in such cases obligatory right-to-light engineer, did the math themselves and came up with three times the amount of space for the client.

Their “Hinterland” project is also about more than just beautiful rooms. They took planning a residential building in Cologne as an opportunity to give some thought the dense nature of the inner sections of blocks of buildings and developed an Internetbased software model. With this, given the floor-space index and site occupancy index, Google Maps data and land registry plans, it ought to be possible to visualize and calculate the maximum possible volume on plots of land. It is intended to facilitate communication between developers, neighbors, the municipal authorities and banks with regard to preliminary building inquiries and cut the cost of feasibility studies. A programmer is currently working on the fine-tuning, and a lawyer on the patent application.

It is perhaps precisely this search for topics beyond the building site that in 2010 won them the prize of the Architectural League in New York, one of the most important for young architects in the USA. They had no desire for the accompanying exhibition to be a show of their projects, but rather one that demonstrated how they work. They had 3D elements of their previous projects, the silhouette of the Wall House or a cross section of the embassy in Belgrade milled from four polystyrene spheres. Driven by the motors that operate glitter balls, illuminated by spotlights and reflected by makeup mirrors from Ikea, the shadows of the spheres were projected on the wall several times their original size. This was a way of working Marc Frohn refers to as “mad science”: understanding, processing, and reconfiguring the context in a way that is unexpected, exaggerated, in fact radical.

They took the exhibition to New York in their hand luggage. Like the models. The suitcases and boxes in which they transported their works to and fro between the continents are in some cases bizarre and are just as much a part of FAR as is the daily Skype session. Marc enjoys talking about the confused looks of the cabin crew when he boards the plane with chain saw containers that have been converted into boxes for models strapped around his shoulder. During out interview there is one of these boxes on the table, in it the very latest FAR project, the temporary Goethe Institute in Santiago de Chile.

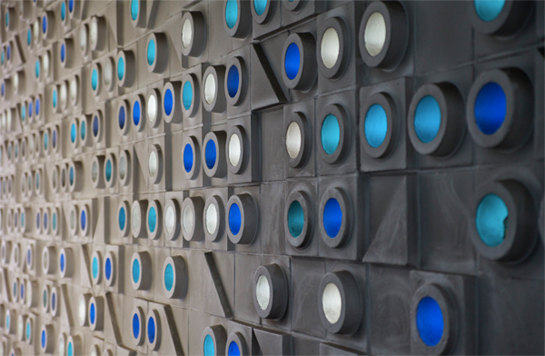

Because the villa in which the Goethe Institute in Santiago is housed has to be refurbished to make it earthquake-proof and bring it up to date with regard to energy standards, a floor with half as much space as in the villa, 17 meters deep and correspondingly dark, has been rented for four years in an office building. FAR has a catalog compiled of all the existing furniture from the old building, made partitions from them and positioned these in a radial configuration corresponding to the incidence of the sun. They countered the standard ideas for prestigious premises with bare technical fittings, an exhibition wall made of acoustic foam, and a moving curtain made of industrial cushions, which a Chilean sail maker sewed together for them. All the rooms boast multiple designs. In three years it will be interesting what far makes of the Goethe Institute’s permanent home, the villa. They won’t just stop at meeting the technical stipulations. The layered brise soleil along the courtyard façade is intended to lead a double life as open-air seating.

FAR recently landed their first contract in Berlin. It involves adding storeys to a building with 19 residential units dating from the 1960s and bringing it up to modern day standards with regard to energy. It is an assignment with model character. First of all, FAR will be asking lots of questions.