Iwan Baan, Robert Huber, Superpool

Profile

For many people Istanbul is one of the most exciting places on Earth at the moment. For years now the city, which marks the border between Europe and Asia, has been growing quickly in all directions. Its now almost 20 million inhabitants strive for eastern and western cultural values, breaking conventions with many of them looking to Europe. Right now, anything seems possible here.

No architectural duo could possibly embody this momentum better than Selva Gürdoğan and Gregers Tang Thomsen. Wearing a black blouse and a headscarf, Selva stands by her desk in the 400-square-meter office suite and pours a cup of coffee. Gregers, tall and blond, sporting a white shirt pulls a couple of chairs over. We have a whole hour for our meeting before the vernissage begins in the new SALT cultural center.

The two met eight years ago at Rem Koolhaas’ studio. Gregers (born 1974) had come from architecture school in Aarhus, Selva (born 1979) from the Southern California Institute of Architecture. In 2006, after four years at OMA in Rotterdam and New York they relocated to Istanbul to found their own studio, Superpool.

What was new cultural territory for Gregers coming from Denmark was a return to her roots for Selva. As a child she lived with her family in Ankara, then in Jeddah in Saudi Arabia, where her father taught at the university, and later spent her teenage years in Istanbul. The fact that the clothes she wears reveal her Muslim faith was perhaps a decisive turning point in her career. Given the ban on headscarves at Turkish universities she was unable to study in her home country. At the Institute of Architecture in Los Angeles on the other hand, it was not an issue at all.

Anyone who fits in with the market mechanisms in Istanbul can do a lot of building there. There is little skepticism towards things that are young and new. In this respect, Superpool’s credentials could not be better: an education at western universities and impeccable references from their time at one of the most respected companies worldwide. On top of which, depending on the client’s preference, coming from two different cultures gives them a strong negotiating basis. But as their projects reveal this was not the reason they came to Istanbul. Selva and Gregers intend to do more than just build; they intend to change the city, and in doing so they are seemingly uncompromising in their approach.

Their portfolio neither corresponds to one’s expectations of a successful architecture studio that has construction project flooding in, nor is it manifested in the size of their building sites and the square meters. Rather, Superpool’s projects are to be found in books and exhibition venues – not to mention on the Istanbul art and cultural scene, whose protagonists speak of the studio as if it were an old acquaintance. There was method behind its selection; it is intended to bring to mind the car-pool lanes in Los Angeles, which are reserved for vehicles with more than one passenger and according to the duo’s credo, architecture, can only emerge as the result of a joint effort from all those involved.

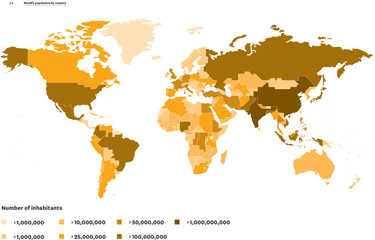

The best example of this is their book “Mapping Istanbul”, which was published in collaboration with the city’s Garanti Gallery, New York graphic designers Project Projects and geographer Murat Güvenç. The maps published in the book, which visualize statistical data on the city and indeed the entire country, were Superpool’s visualization of a previously unknown picture of Istanbul: of the level of education of its inhabitants, the safety of its buildings in the event of an earthquake and land usage. They see such maps as a basis for public discussion on urban development, which is still in its infancy in Turkish culture. Not least of all because the information is not readily available.

People nonetheless find their way in this urban jungle. Somehow. In places that aren’t served by the public transportation system, the gap is filled by private minibus companies, called the dolmuş. Yet woe anyone should want an overview, let alone a timetable. Selva and Gregers spent a year traveling round the most remote corners of the huge city mapping the improvised routes used by the dolmuş. Even if the routes have long since changed, their efforts nonetheless resulted in a website that provides information.

Using visualized information to slowly set changes in motion – the Superpool strategy has already enjoyed success beyond Istanbul too. Their Women’s Guide to Diyarbakir was exhibited at the 2009 Architecture Biennale in Rotterdam. Here they demonstrated how a group of Kurdish women who were ostracized from society in southern Anatolia can be helped in regaining their self-confidence, thereby strengthening the social fabric of a city. On a map of Istanbul they marked the locations and meeting points of aid organizations offering, for example, free launderettes, kindergartens, as well as education and advice on legal and health matters.

Maps and research results, which Superpool distributes on behalf of several parties, are like a common theme that runs through the list of their projects. In this sense Selva and Gregers represent the predominantly western influenced generation of architects, who consider their role first and foremost as a social and political one.

It goes without saying that Superpool is also involved in planning and construction projects. A small house for a family of four is currently close to completion, and on the Asian side of Istanbul, in the up-market district of Dragos Hills, they have designed two high-rises. They are quite unperturbed by fact that the building permission process is currently bogged down in the relevant authorities. This is not an unusual situation for architects in Istanbul; building here is a tough process.

For this reason several projects run in parallel, as indicated by their desk, which is full of polystyrene models. The range of different scales is extreme. On the one hand the two-square meter designs for a small Istanbul carpet maker and on the other those for the three million-square meter master plan for a university in western Turkey. And on behalf of the EU they are conducting research with 14 other partners from universities and manufacturers into a new technology for producing low-cost individual concrete shapes. They decline to give any details, as it is all still confidential. Instead, like a joker in a game of cards, they produce their latest map. Once again it is to do with traffic, which makes its way heavy and aggressive through the hilly city. It is certainly no fun for cyclists, which is why there are hardly any in Istanbul at all. Not yet. Using pink and black graphics, Selva and Gregers have marked those roads which, because of the gentle incline, would be suitable for cycling - and in the process have opened yet another round of discussions.

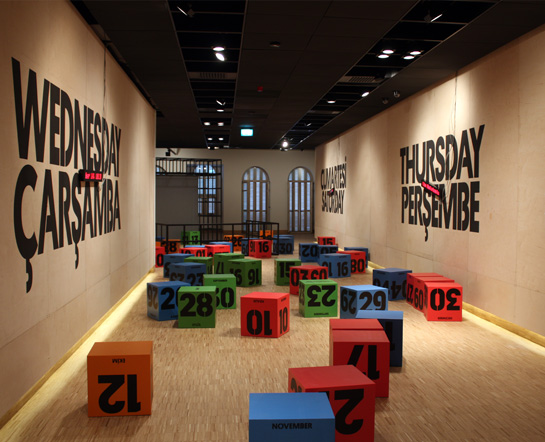

Parallel to the Istanbul Art Biennale their exhibition “Becoming Istanbul” is just opening. It showcases developments over the past ten years from the perspective of photographers, artists, architects and authors. Selva and Gregers have given the presentation, which was displayed in the Architecture Museum in Frankfurt/Main back in 2008, a complete makeover and expanded it to fill the two stories of the SALT cultural center. There is an event planned every day. The exhibition is intended to enter into dialog with the visitors and encourage them to help design the city. As the name Superpool suggests.