Interview

Hani Rashid

Many of the projects you and your studio Asymptote have worked on were from the outset thought of as experimental concepts that would not necessarily end up as finished buildings. What role does this idea of architecture beyond building play for you in it?

I am convinced that there is no architecture without architecture beyond architecture. Because there are many buildings in the world, but not every building is architecture. And many works of architecture are not buildings. For that reason I very much like to use the word architecture as a verb: to architect something. The films of Jean-Luc Godard are perfectly architected cinematic stories. The music of Sibelius is also perfectly architected mathematical mutation.

What makes these examples so special for you?

The way these things are put together. It is fallen into this modernist movement that we tend to assume immediately that the architect puts together a building. But in fact the architect has to put together a number of experts like a film director. What defines us differently from film makers is that we do spatial things. I always liked the fact that a film maker would need a very good camera man, a very good script, even good people on sound with the same issues architects bring together the best engineers, the best people to work with glass, the best people to work with technologies. At the end it comes down to our role in putting all the symphony together of how these people fit into the story. And than the question goes to the architect: What are you doing so special? And that is when architecture beyond architecture becomes important because our only real expertise is “out there” and not “in here”.

So where is the challenge for the architects?

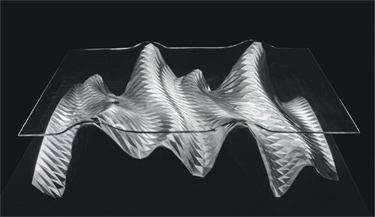

The traditional definition of the architect being a master builder is a very old dead idea. We are much more in a directorial way. My studio in New York is a collaborative. I have lots of great people working who are experts in different things. They are very I very much like to use the word architecture as a verb. Strata Tower Abu Dhabi, UAE Geplante Fertigstellung: 2011 good, very talented. They know what they are doing and have an expertise. But in the end it is the architect who has to mould light, space, metaphysics, poetry or beauty. There is no other expert in that. You cannot go to a consultant for beauty to tell you how to do beauty, how to make the human condition, how to make one inspiring space or how to give a sense of wellbeing. There is no consultancy in that. To accomplish that we have to work on the basics and we have to experiment. I think that is very important. In my studio, however how busy we become, we were always able to find time for experimental work.

I heard you recently moved into your new studio in New York.

Yes, we moved in August and we are really happy because now we have the space for a 500-square meter research lab. We have four floors, and the ground floor is entirely dedicated to experimental work like the pieces we showed at the Biennale. On the back of the success we have achieved we are channelling the money into even more research and experimentation, instead of sitting on our laurels and just having a big construction operation.

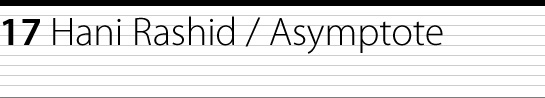

You just mentioned your installation for this year’s Architecture Biennale in Venice entitled “Prototyping the Future”. Could you tell us what it involves?

This issue here is to create an experimental piece that allows us to explore things we have not addressed in architecture for a while now, namely the interaction between the real and digital. How to create a place that is indeed real but that has all the effects, influences and power we find in digital means, be it animation, digital fabrication, or a kind of digital delirium we are interested in. This is an experimental piece I refer to as an “architectural wind tunnel”, where we try to produce certain kinds of effects and attitudes in real architectural space. Something that is inspired by video, by film, by computer but that ultimately is a real physical piece that exists as a model for possible architectural works.

Interestingly enough several of the details are reminiscent of bones and other aspects in nature …

Yes, because we are very interested in the combination of and interplay between the beauty we find in the human body – the notion of symmetry and the way the body works formally – with the technological body like the body of an Airbus A380 or the body of a Formula 1 car. We try to identify the interplay between the technological and the human body. These pieces became hybrid bodies. There is a kind of almost sensual and organic quality to them. At the same time they are built like high performance cars as a result of velocity, movement and speed. That cross is fascinating.

So should aerodynamics be an important criterion in architecture as well?

I don’t think I am alone in this. When I sit in an airplane I become obsessed with the engine and the wings – I can’t help it – it is a beautiful technological result involving the movement of wind. But when you look behind the wings there are clouds, and clouds tend to be the most beautiful formal structure ever seen. They make architecture look very insignificant, this combination of flying, movement and speed, coupled with a poetic, almost romantic idea of human existence. I think there is a sort of the need for repose, for metaphysics, for poetry or for beauty. That is very much part of the human spirit.

What does beauty mean for you?

I think it is changing from a traditional, let’s say western notion. Maternity is changing it, electronic media is changing it, Photoshop is changing it. In architecture we are now looking for that new definition. And again my theses have something to do with discovering why we find certain technological objects beautiful. And it is because of their kinship to nature. There is a very strong link between discovery in form, materials and technology with natural form. But it is different today because of digital technology. Merely imitating a bone or a wing is no longer interesting to us. It is about looking at the dynamics and motion-based aspects of these things.

As a blend of natural and artificial?

Today – and this is a contentious thing to say – there is no nature without technology. My sister is an archaeologist and once told me something I thought was really strange, which I initially rejected. She told me that one of her friends was conducting a research project that was an attempt to discover previously untouched parts of the globe, areas where no human being has ever set foot. She said there are hardly any – not even the peaks of the Alps or the North Pole. Even there we have left our mark. The idea that throughout history human beings have invaded and terrorized every aspect of the natural world, coupled with where we are today in terms of electronic media, medicine, sciences, technology, means that you cannot divorce one from the other. I don’t believe that there is such a thing as pure nature. Because if you say: “yes, there is”, I can take you to the middle of some strange natural place, and a cell phone will ring; having said that, I am not negative about it. But I say: why not find a poetic alternative, where nature and technology come together? As architects the more we embrace it, understand it and control it, the greater chance we have of producing the kind of beauty that is not just a contaminated, polluted older idea of beauty.

I think there are big perils in architecture, which visionary architects have been trying to overcome ever since Piranesi. One of them is gravity and the other is movement. Gravity for some reason never really featured. Movement, on the other hand, whether we are talking about Archigram and their walking cities or indeed our project – the 1988 steel cloud, our first kinetic architecture project – is a kind of a goal. Shape shifting is another goal and a very comparative one. I think this experiment is about how we can make form, changing its density, its velocity, its presence by using traditional means together with digital means. The virtual Guggenheim museum we did is an entire shape shifting museum. And that lingers in the back of my mind, it is a kind of obsession. That’s why those clouds were so interesting.

As a child we all had these dreams where you open the door and go into another room and there is a whole world next to your bedroom. When we ventured into the virtual architecture of the Guggenheim museum we opened that door. We found ourselves in a room of infinite space, with no gravity but lots of opportunity for shifting shape. It was fascinating and amazing. Unfortunately the world was not quiet ready. I think we were a touch too fast off the mark. In ten, twenty, thirty years from now we will find more and more interaction between virtuality and reality. That is what we are researching. But I like being part of this period, because I remember even at school I used to think it must have been a wonderful thing being an architect in 1892, when modern architecture was first emerging, just as it must have been amazing being an architect in Italy during the Renaissance when perspective was discovered.

Your brother Karim Rashid once said that for him the 1960s were pivotal. What about you?

Well my brother and I we were very young in the `60s. Our father, however, took us both to the expo 67 in Montreal, which for him was a completely new world. And I think that in one way or another that infected us both. In our minds we saw an idea of the future we are both, in different ways, trying to get to. At the same time, however, it was a very different period and I recognize personally that those experiments were done, are finished. Next to our work at the Biennale in Venice was Coop Himmelb(l) au’s 1968 cloud installation. I talked with Wolf Prix about it and we had a minor dispute. It was really good fun. I said to him: “Nice to see you’ve got your youth back.” He then said something insulting about my work and I replied that we are now adopting a different approach from his era. And he agreed and said: “This is what we dreamed of!” I think this is a very interesting sign. And I hope that in 30 years time I can look at a younger generation of architects and be able to say: “This is what I dreamed of.”

Thank you very much for talking to us.

Interview: Norman Kietzmann

Norman Kietzmann studied industrial design in Berlin and Paris and writes as a

freelance journalist about architecture and design for publications such as Baunetz

Designlines, Deutsch, Plaza, Odds and Ends. He lives and works in Milan.

project management: Andrea Nakath